I have spent the last week working with all my companies to figure what the business impact of COVID-19 will be. Other people have spent the last week putting their lives at risk in hospitals and clinics. I know who is doing God’s work and it is not me.

That said, we all have our job to do. My job right now is to give the best advice I can to our portfolio companies on how to react to the COVID crisis. This post summarizes that advice. I have tried to avoid valid but not useful exhortation. I will not tell you that the best companies get built in a crisis. Instead–as we all wrestle with budgets that made perfect sense less than a month ago–I want to give you an explicit framework for understanding the decisions that need to be made and some insight on how your investors are likely to be thinking about it.

Every company is going through the same process right now: Admitting Ignorance, Doing the Easy Obvious Steps, and Dealing with the Danger.

See also: we published a Flash Update with data and commentary on Q1 results.

Admitting Ignorance

Forecasting is the wrong word to describe the process we are all doing now. It implies a level of knowledge and precision that simply does not exist. Be humble and recognize that, to a rounding error, “no one knows s*&T”. Instead, be clear that what you are doing is scenario planning in the face of the most unique economic event in history, a simultaneous worldwide voluntarily induced recession.

The known unknowns include: the duration and impact of the pandemic, the impact of the shutdown on the economy (net of stimulus), the damage done to the economy that lasts even after the pandemic, and the availability of equity and debt capital while the crisis is ongoing. And the possibility that next year the pandemic comes back (1).

To even allow for a finite number of scenarios you have to make two high-level assumptions. The first is that the U.S. will eventually curb the pandemic. The proof that this is a solvable problem is that other countries have solved it. We will too. South Korea took a month, so let’s say worst case we take until the end of June.

The second assumption is that the economic cost of beating the pandemic will be a two-step recession, with a shutdown part lasting through June and an aftershock lasting an unknown number of quarters beyond June. The shutdown recession will be weird: superfast out of the gate (economic activity down 50%+ mid-March to mid-April) and highly targeted (i.e. travel down 95% but e-commerce up 20%+). The extent and duration of the aftershock is unknowable right now and is probably the biggest open variable.

The Easy Obvious Steps

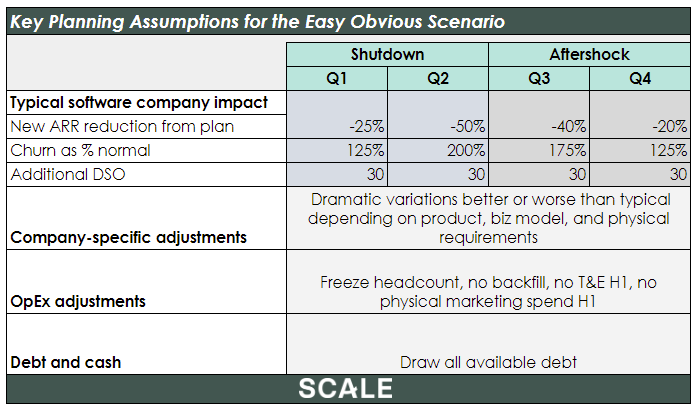

Every team prepares a scenario that I am calling Doing the Easy Obvious Steps, the “EOS”. This is where management:

- Makes estimates for the impact and duration of the recession on the big three of software cash prediction: New ARR, Churn, and Days Sales Outstanding (how quickly customers pay)

- Adjusts those assumptions based on whether demand for the specific company’s product is impacted positively or negatively by the shutdown

- Freezes new hires, eliminates backfills, assumes zero T&E and physical marketing in H1

- Draws all available debt and then calculates the zero cash date (ZCD)

Practically speaking, companies usually combine the first two steps above by implicitly adjusting the “typical scenario” for the specifics of their business rather than calling out the adjustment explicitly. The danger is that this leads to an excess of positive thinking. It is true that many tech companies will see lift from this pandemic, because they enable work from home or e-commerce or cloud development. This is a real phenomenon and we are seeing numerous companies right now that expect to beat their Q1 number.

However, focusing too much on these pockets of strength risks ignoring the impact of the recession on the end customer. Bankrupt non-digital businesses cannot spend money digitally or any other way and the ripple effects of mass bankruptcy and 10% to 20% unemployment will impact even the strongest businesses. Starting with the big picture forces a more realistic view of what is likely to happen.

The numbers in the table above are based on Scale’s early estimates. They are a little more pessimistic than the research Morgan Stanley just released with estimates of the “typical new business” impact by quarter at 10% to 15% in Q1, 25% to 35% in Q2, 20% to 25% in Q3, and 10% to 15% in Q4. However, going back to the first principle above, Admitting Ignorance, I would be the first to say that right now we do not know. Hence the need to run multiple scenarios.

Which assumptions matter most will look very different company by company. A company with a low growth rate going into the crisis will not be that vulnerable to a collapse in New ARR but will be massively impacted by a churn spike. Conversely, a high growth super-early-stage business has no revenue base to churn and thus is way more exposed to a New ARR hit. This is obvious when you say it, but I have seen multiple board calls where (admittedly) busy venture board members compare the planning assumptions of a $10MM, 100% growth company with those of a $50MM, 20% grower when in fact the key driver in each is very different. Figure out the highest impact assumption and focus on that.

(Q1 Flash Update: the overall numbers above seem correct based on early reports for Q1. The most striking data shows an even greater dispersion of results than we had thought. Some companies with “must have” initiatives for the move online beat their number, others, where the customer base itself is troubled, missed by 75%. In forecasting, the clear message is to anchor off the reality of an overall recession but adjust based on a granular understanding of the need for your product right now, the financial health of your customers, and your ability to physically sell to and install your product.)

Dealing with the Danger

“Danger is the narrowing of choices” (courtesy of The Perfect Storm). The closer your Zero Cash Date, the fewer the choices and, thus, the greater the danger. After you’ve run the Easy Obvious math your cash out date will fall into one of three buckets:

You need money in less than six months. You are in acute danger and waiting it out is not an option. You need money now. Being more optimistic about the duration of the aftershock is not an option. You are out of money before it matters. The Easy Obvious Steps are not adequate, and you are going to have to find more cash. There are only two options and you will probably need both. You will have to dramatically cut back costs, even at the expense of future upside. And you will also likely need some insider support (if possible) to give you the time to make those changes.

You need money between six and 18 months. You have choices but what do you do? Companies in this bucket face the most complex choices. Do you bet that the aftershock does not linger and you can raise capital in 12 months? Or do you cut expenses beyond the Easy Obvious Steps and push your cash out date beyond the 18-month mark? If you cut more, how much is too much and how will it impact growth? If you bet on an early recovery and you are wrong, can you still recover or have you put the company in danger? Do you and your investors have a shared perspective on that risk? Or, to ask the question more bluntly, if you bet on a more optimistic early recovery and are wrong, will investors be willing to write a check to cover the resulting cash hole? This is all about having a shared consensus on risk vs. reward.

You are cash flow positive or have 18+ months cash. This one is easy. Play to win. Continue to invest in R&D, trim other costs as required but without a gun to your head. Give your team the confidence that comes from knowing they are with a winner and use that confidence to sweep the market.

If you are going to opt for 18 months cash only, rather than pushing all the way to CFBE, you should think carefully about what you will look like in 18 months when you have to fundraise. If the inevitable hit to growth you take during this crisis will make that fundraise hard, as you will not be growing fast enough, then you have no choice but to push harder to get to CFBE. It’s a super tricky tradeoff and requires a whole other post. (But still a relatively high-class problem right now.)

How much insider support should you expect?

The unanswered question in all the above is what level of insider support is available. The company needs money, the board is made up of venture capitalists, and venture capitalists have money to invest. Why not–thinks every management team–just give us the money to get through the crash? Especially for this bizarre crisis that is “no one’s fault”.

Because this conversation is difficult to have directly, it is often done indirectly. Arguments about the need to cut “unnecessary” costs become a proxy for a statement about insider unwillingness to fund. The result is a frustrating lack of clarity around the table about what level of support is realistic.

I am a huge believer that direct hard conversations are a lot better than conflict avoidance, so here are my thoughts on inside rounds right now.

First, every venture investor would do well to remember the human cost of what we are talking about. We are not dealing with people’s lives but we are dealing with their livelihood, and phrases like “cut the burn”, thrown out in a cavalier pseudo-tough fashion, do not capture the impact of this on the people involved. These are people we all collectively recruited to join this mission and now we are having to terminate their employment.

The scale of the crisis provides the macro answer to why inside rounds will be hard: insiders can’t fund every company that needs money. Given that reality, what venture firms are doing is financial triage, a metaphor that now sadly everyone understands. Just like medical triage, this is tough to talk about, but you are better off for knowing how most venture firms think about portfolio management.

Even in good times, maybe only 20% of a portfolio is doing so well that they are in the all out “spend what it takes to grow” mode. The other 80% are still proving something out (product, GTM model, growth strategy) and the idea is to make the existing capital last until the next proof point. At that point the company can go out and raise its next round.

Every venture firm worth its salt knows which deals are home run deals where it is a mistake even in a downturn to cut back on growth, which deals are solid deals that will return a decent multiple but are not on track to return the fund, and which deals are not working out. The first group gets generous capital even now, the second gets limited capital but should get some, the third gets none. Venture capital is not a Lake Woebegone business—most of our deals are in fact below average.

Let’s assume your company is in that second category and your ZCD is 18 months or less. What does it take to get insider support and how should you do it?

First, you have to be able to convince your VCs that you have reduced spend to the point where additional cuts will do more harm than good. Framing the opportunity cost of additional cuts is often helpful. We like to know what the marginal dollar is buying and we like to know that you are serious about scrutinizing the burn.

Second, you have to understand what is realistic around the table. Big funds can be overextended, some funds won’t have money, and others hate inside rounds (2). In most cases, the capital around the table is not going to be enough to fund an aggressive plan in any scenario. Average together those situations and you likely won’t get enough money to swing from the fences but you may get enough to live to fight another day.

Third, the only way to get a round done is to make it attractive for investors who want to support the company while being fair to investors who cannot. Any money you raise now is going to be very expensive capital. Existing investors, especially those who cannot play, are entitled to push back to make sure the company needs the money. If the value created from the additional cash is less than the cost of that capital the company is better off not raising equity. Equally, the math has to work for investors putting in money now. This is usually an arduous back and forth process but a basic rule of economics is that price clears all markets. The one number that is not relevant is the price of the last round.

Fourth, it can often help to use your scenario planning to drive consensus. Especially at a time like this when what we know is so limited, it can help to have a two-step plan with the second step based on what we learn say between now and June 30th. This flies in the face of the “do it all, do it once” school of cuts but I stand by the opinion that in the face of monstrous uncertainty a Bayesian approach to decision making–adjusting as new information emerges–is in fact the right approach.

What you are entitled to as a management team is clarity from your investors. I don’t blame another investor for saying, “Not a dime more because I just don’t see the upside from here.” I do blame the investor who is unwilling to give a clear answer.

This is a tough time but it will end. Things were never as good as they seemed last year, and they are almost certainly not as miserable as they seem today, working from home, worried about loved ones, and dealing with the economic fallout. I wish you all the best in wrestling with this.

Footnotes

- If you feel an urge to have a detailed opinion on any of these issues then please read this (very funny) article on the current outbreak of DKE. DKE, the Dunning-Kruger Effect, is when people overestimate their cognitive ability and their ability to assess data. If you find yourself having an opinion on the epidemiology of COVID-19, ask yourself, as my wife asked me recently, when did you graduate from medical school?

- This also explains why many VCs say, “No inside rounds.” It is a lot easier to start with a blanket no and then work back on a case-by-case basis. This is also the real brilliance behind something like the famous Sequoia RIP Memo that proclaimed the end of good times in October 2008. At that point, the S&P was at 880 and sliding fast. The trough came less than five months later at 666 in March 2009. The index was back above 880 by July 2009. The subsequent decade 2010-2019 was one of the best stretches for the equity markets in history. As a global macro call, this was not correct. However, as a call to action it was entirely correct. Cut the burn, save yourself, no one including us is going to save (most of) you. The same message applies today. Often when VCs talk global macro they really mean no.