Platform shifts create explosive venture outcomes. Within two years of the first iPhone, the new mobile platform led to the inception of consumer applications like Uber, Square, and WhatsApp. In parallel, public cloud was catalyzing the early days of enterprise SaaS apps, with Box, DropBox, HubSpot, and Slack all getting off the ground with funding before the second anniversary of EC2.

With so many applications becoming dependent on fundamentally new technologies, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that a platform shift would necessitate a new infrastructure stack. It feels only natural that a change of such magnitude would require purpose-built technology to deploy, optimize, and secure this new way of building. So, like clockwork, every platform shift has been accompanied by a flurry of funding for tools sold to developers, IT, and security to help better utilize the new technology in question. We have seen it with cloud, we have seen it with mobile, and in 2024, we are seeing it more aggressively than ever before with the coolest kid on the block, “AI infrastructure.”

The way that investors have explicitly demarcated and priced AI infrastructure as a category suggests that the prospective opportunities merit consideration as an entirely separable and exceptionally lucrative market compared to the rest of infrastructure. But if history serves as a lesson, these platform-specific infrastructure bets do not actually bear fruit the way we think they do. And as we look back at the opportunities that did yield generational outcomes during these periods, it is worth thinking about what they did right and what signals point toward success for early infrastructure startups today.

Historical infrastructure outcomes on the back of platform shifts

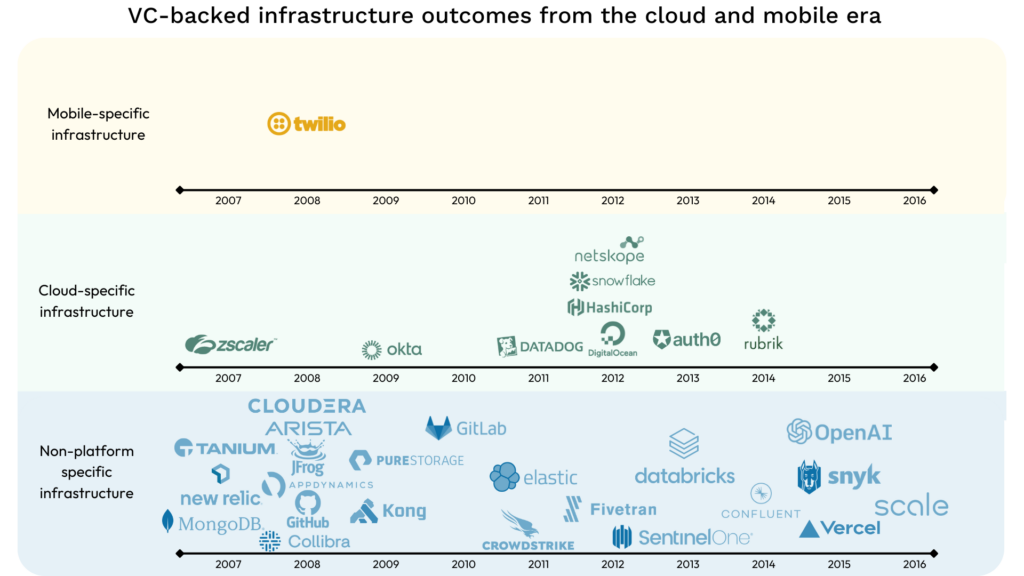

The ten years that followed the release of AWS and the iPhone were one of the most prolific periods we have seen for venture-backed software infrastructure outcomes. But where did these outcomes actually come from?

Before diving in, it’s helpful to start by thinking about how everyone has been defining “AI infrastructure” as a category today. The archetypal AI infra markets include categories like LLMOps, Vector Databases, AI Orchestration Frameworks, AI security, and so on. These companies are relevant if and only if customers are building AI enabled applications. Equivalent outcomes have been formed around platform shifts of the past. Cloud security providers like Netskope and Wiz were created to address vulnerabilities that uniquely arise when applications are in the cloud. Companies like Okta and Auth0 formed to solve the unique identity and authentication requirements of cloud and SaaS based applications. It is important to note, however, that what distinguishes these companies is not the platform they are built on top of, but rather, the platform they enable others to build on top of. When we talk about platform-specific infrastructure bets, we are talking about tools that become relevant when and only when others are trying to build on top of the new platform in question.

With this in mind, when we look back at what happened in the infrastructure market around cloud and mobile, the majority of success stories from this period were not actually these dedicated cloud-specific or mobile-specific solutions that were purpose built to help others build on top of the new platforms. They were solutions for established problems that were relevant with or without the new platforms.

Now, before you start going on about how “mOnGo AnD nEw ReLiC wEre cLoUd oUtCoMeS”, you might want to look back at New Relic’s Series B announcement, or Mongo’s Series C announcement , control-F for the word “cloud,” and see if you find anything.

To be abundantly clear, we are not trying to deny that the platform shifts happening in parallel were eventually used by these companies and contributed to many of their ultimate successes (more on this later). But companies like Mongo were already well on their way to being big and would just deploy however their customers wanted — originally on prem and later with cloud. This is different from a company like HashiCorp where the growth was fundamentally catalyzed by a change in how we interact with servers because of the cloud.

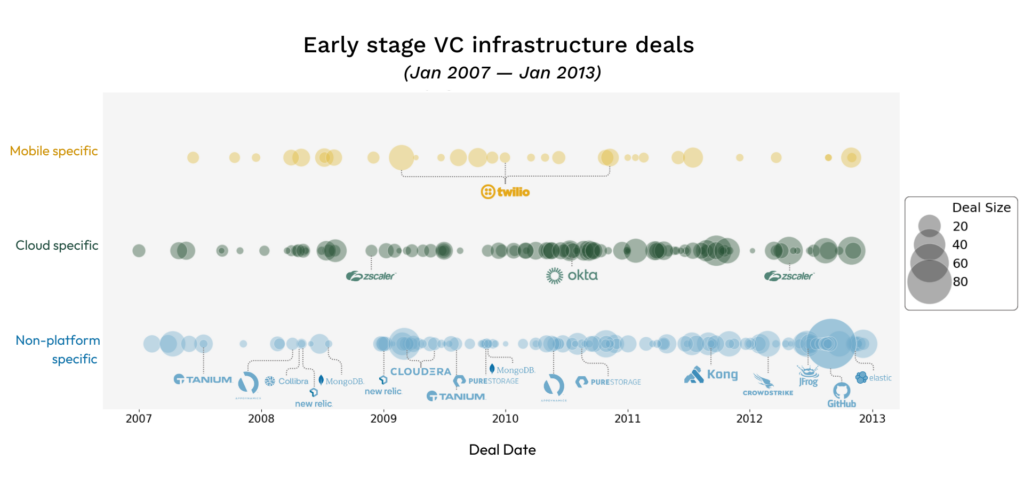

The reason we have been so firm in making the distinction between platform-specific solutions and the rest of the infrastructure market is because it is the one that VCs seem so keen to make when these new technologies come onto the scene, and it is the distinction we have made around AI infrastructure today. Many remember the days of early cloud when investors would hound to fund a company like Rightscale, Eucalyptus Systems, Cloudpassage, or Cirtas that was taking on the task of helping others secure, optimize, or build on top of cloud. There was similar activity around mobile, with companies like Appcelerator, Sencha, Skyfire Labs, and ItsOn all trying to help customers bridge the old and new.

In the end, however, for mobile, many processes did not end up being materially different from web and desktop, and a substantially new stack was not really required. Aside from Twilio, which identified a mobile-driven change in consumer behavior that required a unique solution in order for enterprises to take advantage of it, other startups failed to achieve returns of equal magnitude.

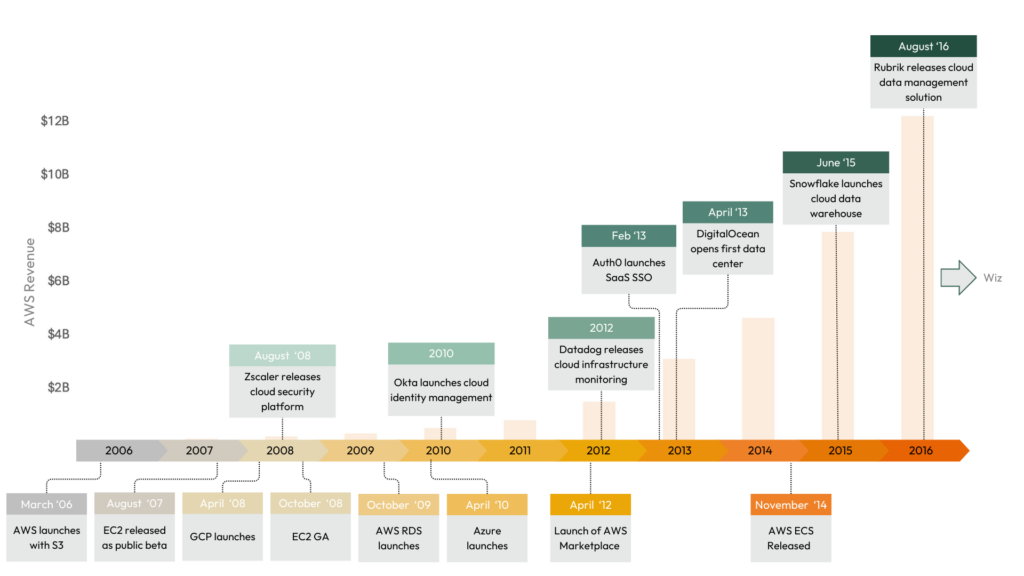

In terms of cloud, there were substantial returns in the end, but with the exception of Zscaler offering cloud security and Okta cracking cloud identity, the companies that provided the biggest outcomes did not really get started until 5+ years after the launch of AWS. In order for the market to understand the value proposition of a company like Snowflake, a data warehouse that could decouple cloud storage and compute, or DigitalOcean, a more abstracted and developer friendly cloud platform, patterns needed to be uncovered, and buyers needed to reach a certain level of maturity and awareness. And let us not forget Wiz, a company that is shaping up to be one of the biggest cloud infrastructure outcomes yet that was not even founded until fourteen years after the launch of AWS.

However, investor behavior in the early days of cloud and mobile did not reflect patience or prudence that aligned with these trends. While very few platform shift-specific infrastructure startups funded between 2007 and 2012 would yield multibillion dollar outcomes, there were nearly fifteen infrastructure companies started elsewhere in the market that would. It was not that money dried up for startups that were in the latter group, but the number of deals done in mobile-specific, cloud-specific, and non-platform specific infrastructure was in no way proportional to the number of outcomes each category would ultimately yield.

Looking back to think through these outcomes has nothing to do with shaming the past. Venture capital is about being a believer and taking risks, and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. But are we actually learning from our mistakes?

Today’s mania: AI infrastructure investing

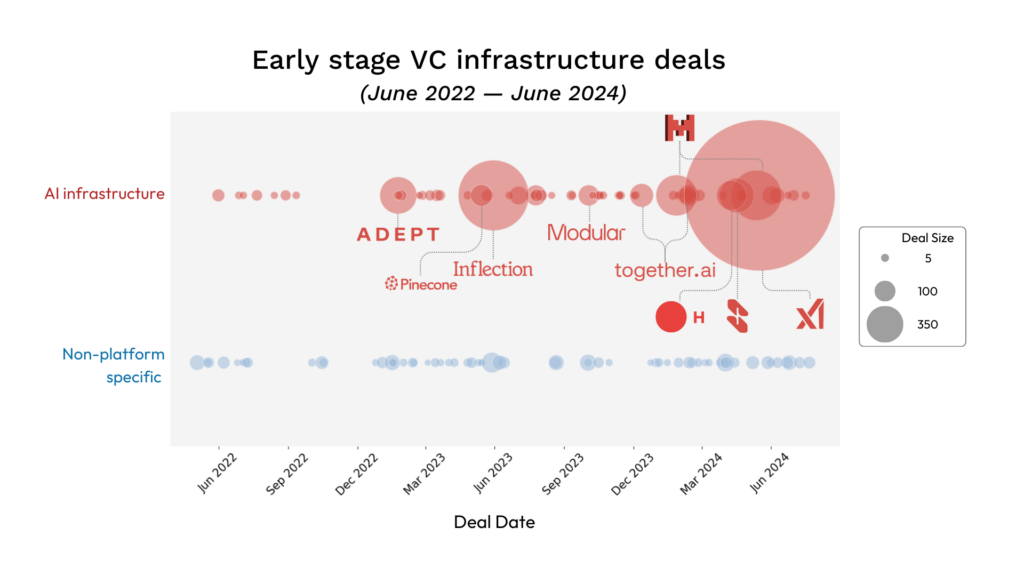

It is no secret that the AI infrastructure market is a madhouse. Looking at today’s version of the previous early deals plot shows this loud and clear.

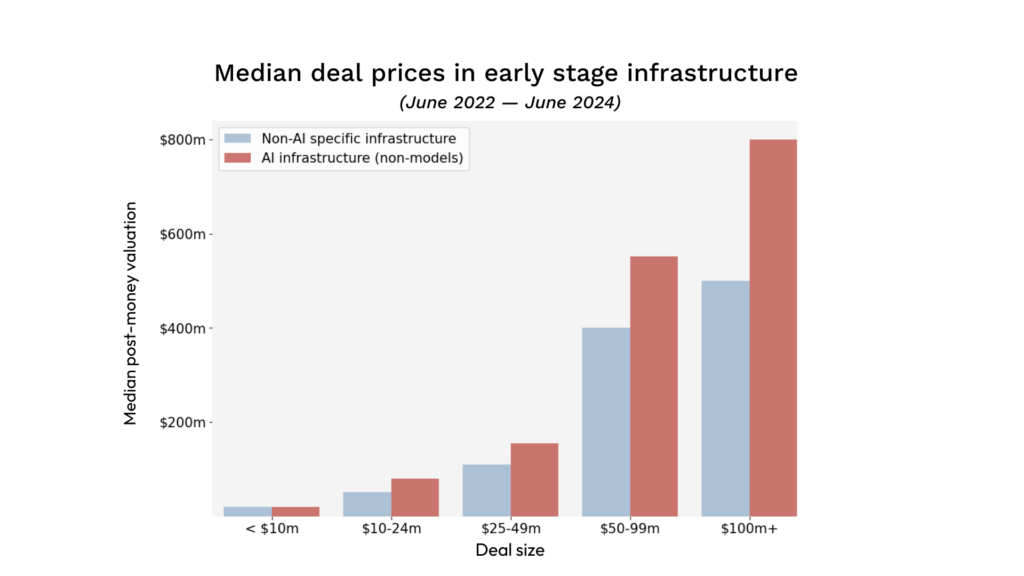

What is striking is not only the number of deals being done, but also the sheer magnitude of the round sizes, prices, and revenue multiples they are clearing. Many of the most startling examples are foundation model bets like Mistral and xAI, but even when you exclude these model providers from the picture, the price discrepancy remains glaring.

Crazed hype driving irrational valuations is not the only factor to blame here. It’s worth remembering that during platform shifts of the past, the hardware layer was mostly left to the hyperscalers. But today, in addition to the model providers, many AI infra startups like Together.ai, Fireworks, and Modular also involve expensive hardware build outs that demand massive rounds. The semi-fixed relationship of valuations and capital in venture markets mean that these megarounds have led to unprecedented valuations across AI infra, with surprisingly little adjustment for the associated risk. The results have created extreme price expectations and distortion in the rest of the market.

It’s easy to argue that this is just the price you pay to underwrite generational opportunities in an increasingly competitive venture market. But paying $300m+ for early deals with 20+ well funded competitors before the second anniversary of ChatGPT is an inordinately far cry from Okta raising $16 on $78m in 2011 or Snowflake raising $20m on $75m in 2014. And when we think back to where the most VC-backed infrastructure value actually accrued during past platform shifts, it is worth asking ourselves if we are fishing in the wrong pond or in a pond that hasn’t been stocked yet.

Where platform shifts do create infrastructure opportunities

Even though most of the generational infrastructure companies born in the early days of cloud and mobile were solving problems that were not specific to these trends, many of them benefited from the shift to new platforms.

Flexibility & adaptability

Platform shifts create new ecosystems, and the companies that move fast to integrate these new technologies are able to serve customers across increasingly varied stages of maturity. Take this quote from Mongo’s 2013 fundraise announcement:

MongoDB isn’t intended to be a cloud-only database. It’s a general purpose database, designed to be a great fit for the vast majority of workloads. We want to make it easy to run on a single node or at massive scale in the cloud or on premise. Whatever the customer needs.

Companies like Mongo may not have been solving problems unique to cloud, but their ability to identify market tides and provide a truly platform-agnostic solution has been crucial to their success. Many customers eventually preferred a cloud-based solution that absolved them of on-prem deployment responsibility, and Mongo adapted accordingly. Nearly a decade later, Mongo has continued to evolve and sits alongside other incumbents topping charts in AI’s VectorDB market. In many ways, these platform shifts just amplify the normal adapt-or-die survival conditions.

Auxiliary tailwinds

Platform shifts also often increase development complexity across the board and reinforce demand for solutions that make developers lives easier writ-large. Take Scale portfolio company JFrog. The company was founded in 2008 to provide binary management software, a DevOps solution that is relevant regardless of where you are deploying. The problem space is not unique to the cloud, but cloud environments do make the deployment process far more complicated and far less secure, and many companies have been forced to adopt a solution faster than they otherwise would have as a result.

We believe that similar conditions have the potential to accelerate DevTool outcomes today. Our portfolio company, Cortex, provides an IDP, an engineering system of record that serves as a central hub for engineers to track, improve, and build top-tier software. A number of existing trends have already made purchasing Cortex a no-brainer for top engineering organizations. But in a world where AI changes the way developers work and proliferates the amount of software being deployed, we expect tools like Cortex will become indispensable. Better documentation, better organization, and better systems of record not only make engineers more productive and reliable, but also make software producing AI agents more productive and reliable. A system that is the context holder for developers today has the power to become the context holder for AI in the future.

AI will change the SDLC just like the platform shifts that came before it. And like these platform shifts of the past, many of the best DevTools only stand to benefit.

First order problems and head starts

As we touched on earlier, many problems will only crystallize after the market adopts a new platform. A few problems, however, are more first order, and these arise as the market adopts a new platform. Conveniently, there can also be precursory trends that predate platform shifts and provide lucky witnesses with prescient insights into what these first order problems will be.

Okta founders Todd McKinnon and Frederic Kerrest were on the front lines of Salesforce’s migration from on-prem in the cloud-before-public-cloud era. They got an unpleasant preview of the issues traditional identity tools would cause in a cloud-native world. It was clear that the lack of a SaaS and cloud-native identity provider would not merely be a pain, but likely a prohibitive bottleneck that could prevent companies from moving applications into the cloud all together. It led them to a cloud directory solution that is behind many of the cloud applications we know and love today. Our friends at BCV dive into Okta’s history nicely here.

Comparable opportunities to solve first order problems will materialize in the world of AI, and there is once again a select crop of founders that have had early previews into what they will be and how to solve them. Disentangling what is truly first order from the rest of the noise is easier said than done, but it is fundamental to the investment decisions we are making in this market. These are the diamonds in the rough.

Patience

Ultimately, it took five years after the launch of EC2 for Snowflake, Netskope, and DigitalOcean to get started. It took seven for Rubrik, and fourteen for Wiz, and there are still untapped markets in cloud infrastructure today. When it comes to platform shifts of true magnitude, second, third, and fourth order problems can arise that make these markets almost evergreen. But that also means that sometimes, it can just take time. There is, afterall, such a thing as being too early. Opportunities that might not be first order today may very well have their time in the sun in due time, and patience will prove its virtue.

What now?

It is unwise to look at the past and conclude that it didn’t happen then so it won’t happen now. There is no rule that prevents uniquely perceptive founders from identifying enduring trends and delivering at any point in time. But as investors, that does not mean we should ignore the reality of the past and be blind to what is happening today.

I believe there will be generational AI companies. I believe there will be generational AI infrastructure companies. One way or another, the infrastructure market has produced unprecedented outcomes during platform shifts of the past. I believe similar opportunities exist in and around AI, and the founders taking risks to make it happen should be applauded. But today, our behavior as investors also seems to suggest that the new and shiny solutions are sure bets and it’s now or never to do them, and that, I categorically do not believe.

Implicit in our excitement for AI is our belief that it is here to stay. Exceptional founders will continue to capitalize on these changing tides in various shapes and forms. It is our responsibility as investors to create the market conditions that can support them.