Why would anyone invest in a hits driven asset class that has yielded a negative IRR for the past ten years; where there are only a few good firms, and they are not taking new investors?

That is what is weighing on the mind of many of the LPs we met in our recent fundraise. As yet, there are clearly LPs investing in venture, including newer managers like Scale Venture Partners. I would like to think our investment performance and our engaging smiles made the difference, but no institution would have invested in ScaleVP unless it first of all believed in the asset class and had answers to the questions above. What are they seeing that others are not?

Long term returns in venture are strongly positive

It is true that the pooled mean return for venture for the last ten years (2001 to 2011) is dismal at 3.3%, (and was -2.0% as of end 2010), but it is also true that thepooled venture return for the past twenty five years (1986 to 2011), even including the last ten bad years, is strongly positive at 18.6%. This mid to high teens return is the kind of outperformance relative to the Russell 2000 index, which has returned 8.7% over the same period, required to justify the extra risk and illiquidity of venture capital.

U.S. Venture Capital Returns

End-to-End Pooled Mean Return, Net to Limited Partners

(%)1-Year10-Year25-Year 2011 Cambridge Associates U.S. VC Index13.183.2718.61Russell 2000(4.18)5.628.68 Definition/Sources: [1] The Cambridge Associates Venture Capital Index is an end-to-end calculation compiled from 1,347 U.S. venture capital funds formed between 1981 and 2011. It is a “dollar weighted” index that best represents the aggregate return of the entire venture industry.[2] The Russell 2000 Index measures the performance of the small-cap segment of the U.S. equity universe. It includes approximately 2000 of the smallest securities based on a combination of their market cap and current index membership[3] NVCA Benchmark report

LPs we spoke to, who continue to invest in venture, implicitly believe that the next ten years will be more like the average of the last twenty five years than a repeat of the last ten. In short, they are betting on regression to the mean, which is almost always the likely bet in investing.

Narrative Matches the Math

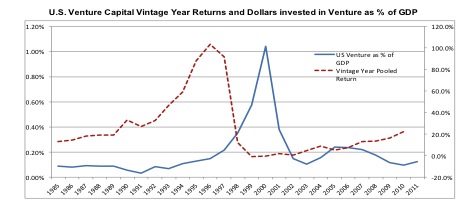

A bet on regression to the mean also tracks a simple narrative of the past twenty years that we have blogged about before at ScaleVP. The terrible results of the last decade are not a mysterious affliction of unknown origin, but rather the result of the stunning results of the ten years prior. The story starts with sensible levels of overall venture investment in the early 1990’s (at approximately 0.1% of GDP), generating exceptional returns (the pooled IRR for 1995 was 88%), money rushing in (2000 fund raising grew tenfold to 1% of GDP), and returns inevitably plummeting. Capital then started to leave the industry but slowly. It has only been since 2008 that the capital raised by the venture industry has returned to that 0.1% of GDP level that was so profitable in the early and mid-1990’s. Specifically, in 2012, the industry raised $20.6 Bn which is .13% of US GDP for 2012, just as in 1995, the industry raised $9.4 Bn which represented .13% of the US GDP for 1995. As discussed above that was a successful year for venture! The graph below illustrates the trend, and the comment that “there is still too much money in venture” is now simply not correct relative to GDP. The industry took a far longer time to adjust than predicted, but with a decision cycle only once every four years, in retrospect that is not surprising. The strong performance of funds in the last few years is plausible, though still early evidence that the long-term dynamics of the business are improving.

Investing in a hits driven world

Even many of the LPs we spoke to who are not investing in venture would agree with the analysis above. What LPs really wrestle with in venture is how to build the right portfolio to get that venture return. Venture returns are concentrated (“a hits driven business”) and are persistent (“only a few good names”). The risk that an LP does not get access to the right names, and ends up missing the few great companies that make all the difference, is what turns many LPs off the asset class. “If I cannot get access to Sequoia, (or fill in your favorite name), then what is the point?”

However, LPs who have continued to invest in venture have a more nuanced perspective on concentration and persistence, and thus what portfolio strategy is viable. Take the extremes. If returns were 100% persistent and 100% concentrated only one firm would make all the money, all the time. The only sensible strategy would be to invest in that one firm, or not to invest at all. If returns were 100% concentrated but zero percent persistent, such that every year only one deal makes money and it is random by fund, then the best strategy is to invest in every venture fund, every year, to be certain to get the pooled return, or not to invest at all.

Exploring the extremes illustrates the point, but most investors agree that reality is where returns are both concentrated and persistent but neither metric is close to 100%. In that world, the rational portfolio strategy is to build a portfolio with significant access to known, persistent top performers, but with enough portfolio diversification in newer managers to ensure that the fund does not miss out, if the out-performers turn out to be the newer managers. A strategy of just investing in the “five top funds” runs the risk that, if concentration outweighs persistence, an LP is under-diversified and could miss some home run winners. A strategy of investing in fifty plus venture firms is over diversification, and will likely result in underperformance if exits are concentrated in a smaller number of firms.

How concentrated and how persistent?

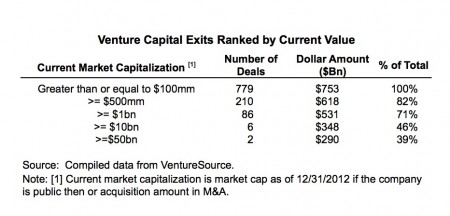

At ScaleVP, we have made estimates of both return concentration and return persistence. Return concentration is relatively easy to estimate, and no surprise, returns follow a rough power law with a few huge wins and many base hits. There have been 779 venture exits valued at $100M or above, in the last decade, but the current market capitalization of the top two companies (Google and Facebook) at $290Bn, equals the sum of the value of the bottom 739 exits. Miss the top eighty-six exits, (valued at over $1Bn) and you have missed 71% of the total value created.

Firm persistence is harder to measure without individual fund level data, but it is clear that some firms manage to deliver great performance for years and even decades, but some old firms, like McArthur’s old soldiers, never die, they just fade away. Because an ability to fundraise based on prior performance is a lagging indicator, firms can still raise money even with an investment performance that does not compare to newer, more focused firms. In the face of this, LP outperformance has to come in part from pruning firms as they underperform, and increasing commitments to firms that are doing well. Change is slow in venture. It is a lot easier to maintain an existing winning firm than to build a new one, but change does happen and the successful LPs are ahead of that curve.

What it meant for our fundraise

The comments above sound theoretical, but they correspond with the reality we found on the road. Our typical LP has either maintained a long term commitment to venture over the past decade, or even more interestingly, has been contrarian and elected to increase its venture exposure in the past five years when others were exiting. Most have a portfolio with a critical mass of proven venture relationships (or access to same via a fund of funds investment). Even though it is harder as a newer fund to win support from an LP with a strong existing portfolio, these are also the LPs that have enough success to maintain investment committee support in difficult times. The reverse was also true. LPs who have had a negative overall experience with the asset class, were rarely interested in adding new names. It’s just like in real estate, where you don’t want to be the best house on a bad block; for a GP, you don’t want to be the best performing GP in a bad portfolio because your neighborhood may not survive.

Our typical LP is an activist about their portfolio. Despite having a base of good names, they are believers that smaller, newer funds can outperform and are willing to take the risk of trying newer names, and then doubling down on winning firms as they prove themselves.

Finally, our typical LP knows that investing in venture is not easy and does not expect it to be. The prize is an 18% pooled return over twenty five years versus a Dow return of 10% in the same period. Accessing that return requires effort, persistence and perhaps a little luck, but it is a level of equity outperformance that is simply not readily available anywhere in the investment universe.