Can you imagine steering a car and getting directions from a manic depressive in the back seat? Most venture-backed CEOs can. Can you imagine how stressful it would be if you had to play nice to that person because they have the money to pay for gas? Most CEOs know already.

The venture industry, and the capital markets more broadly, are that manic depressive back seat driver. In November we said your startup was worth over 50 x revenue. Today we are saying 10 times is too much, and you need to get to cash flow breakeven right now. The obvious question: how much should you listen to advice from people that got it so spectacularly wrong six months ago?

Listen but Filter

Should you do exactly what we say? Hell no. Our stock in trade is valuations. When valuations are up, we are happy, when valuations are down, we often panic. Can you ignore us entirely? No, because we have the gas card. The reality of running a high-growth startup is that you are almost certainly going to burn money, which means at some point you need to know what the manic guy is willing to give you.

What you should do is listen but filter for what matters to you. Right now, the default venture missive is a combination of fact (valuations are down), prediction (we are going to have a recession), and advice (you should cut the burn). The fact is true, the prediction is probable, but the advice needs a lot more massaging to be useful. Here is my mental model for what is going on:

Fact: Tech Valuations are down (a lot)

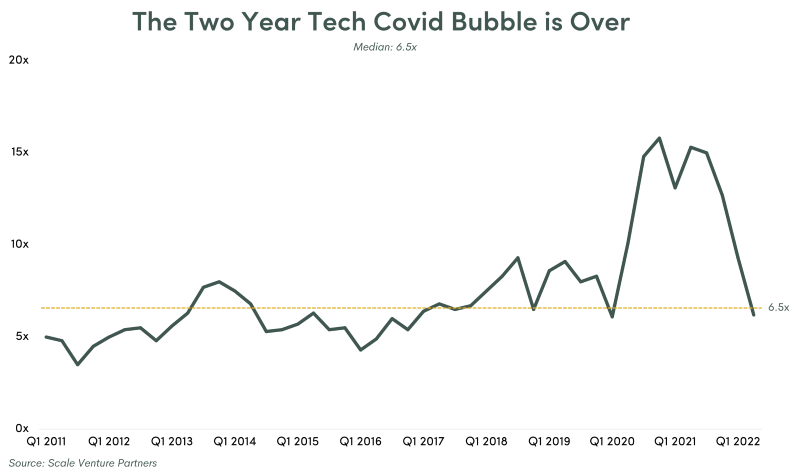

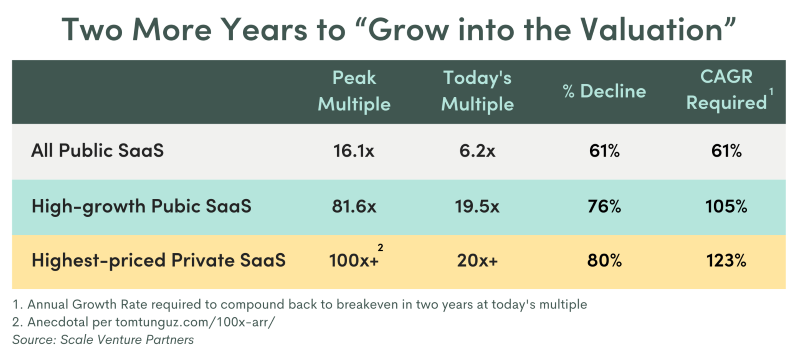

Public Tech valuations have just done a massive two-year-round trip during Covid. From peak to today public SaaS multiples are down over 61% to just below the long-term median of 6.5x and high-growth public SaaS multiples are down an even larger 76%. Private company valuations are by nature harder to track and slower to correct, but the anecdotal peak 100x ARR valuation of 2021 could be due for an 80% correction. The Covid Valuation bubble is well and truly over.

When investors overpay by 5x it takes two years of 123% growth to “grow into the valuation” as the phrase goes. The table below shows the math. This growth rate is not impossible, but it is not the norm, and so many companies will face the (not awful) prospect of a down round. We have just lived through one of the great epic bubbles of financial history. Even if nothing else was wrong with the world, cleaning up this mess would be a rolling problem for the next two years.

My guess is also that the venture angst right now is less about a firmly held prediction for 2023 GDP and more about a slowly dawning recognition of what a big hole the industry has dug for itself in the last two years. It’s that moment you wake up after a wild fun evening and start to come to grips with what you did at the party.

Prediction: A recession is coming (but what flavor of recession?)

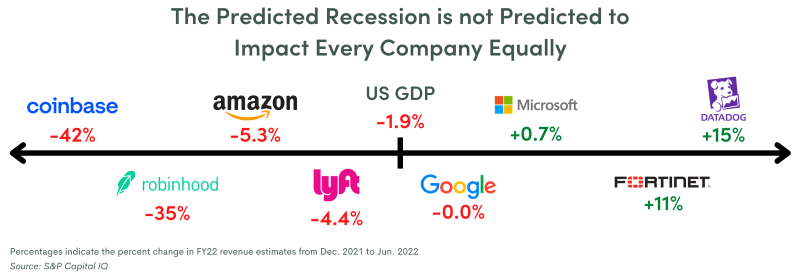

If the plan is to grow our way out, the bad news is that pundits, including venture investors, are predicting a recession. Predicting recessions is hard, which does not seem to stop everyone from trying. Macro forecasting exists, as Galbraith said, to make astrologers look good. However, thinking about a “recession” may not be the most useful way to think about what is going on now. It implies a one size fits all world, but we are not seeing a one size fits all reality.

Look just at how 2022 revenue guidance for these public companies has changed between Dec 2021 and June 2022. This is the period when we went from a recession being perceived as unlikely to being seen as almost inevitable. In that period, the Coinbase 2022 consensus revenue number was reduced by 42%, Amazon’s revenue estimate came down by 5%, Q1 GDP was down 1.9% and some of the best software companies are predicting higher revenue for FY 22 as of June, then as of last December. We should take all predictions with a grain of salt and there is probably bad news to come but it is the spread of the predicted impact that is noticeable.

We are seeing the same story in our portfolio

- Companies selling labor-saving automation to corporate America are seeing revenue acceleration as labor shortages drive the need for automation.

- For core SaaS companies it depends on the health of the end customer. SaaS companies selling to other venture-backed companies are seeing significant slowdowns driven by the valuation reset above. Companies selling to larger corporate customers outside the tech ecosystem are doing much better as corporations continue to invest in technology.

- Companies with exposure to, or directly based on the most speculative or venture-fueled sectors (crypto, consumer lending, rapid consumer delivery, etc.) are seeing absolute revenue declines.

I am not Pollyanna. An extended cyclical downturn will impact all startups but the key is that it will not impact all start-ups anywhere close to equally. How we got to this point was weird (Covid itself, unprecedented Fed expansion, a tech valuation boom, lockdowns, shortages of goods, inflation) so it makes intuitive sense that the unwinding will be weird also. One of the mistakes forecasters make is trying to group and compare different downturns as if there were only a few flavors of bad, when in fact, every downturn is unique and different. This is not Global Financial Crisis (II) or even Dot.com (II), this is yet another completely different way in which the world has become screwed up. It will unfold in its own special way (my gut is a shallow but long grind v a short deep shock like the GFC).

Tech investors may not be best positioned to assess the wider economy right now. There is a clear linkage in tech from the valuation collapse to a slowdown in tech revenue growth.

Companies that are laying off employees to avoid raising capital, do not simultaneously invest in new software, so one startup’s expense cuts become another startup’s revenue slowdown. This is the tech reality, but it is not the reality (yet?) in the 90% plus of the economy that is not tech. Put another way, I think over half of the “recession pessimism” coming from venture is based on a justified pessimism about the revenue consequences of the valuation reset and not from a dubious ability to predict the wider economy in 2023.

In practical terms, it means that management teams should not focus on a generic macro prediction about a recession. Instead, they should focus on having a firm grasp of what is happening to their customers and in their end markets. Macro forecasting is meaningless, Revenue forecasting is what matters. Don’t worry about the money supply, worry if your customers have money.

Advice: Prioritize Runway over Growth, (maybe?)

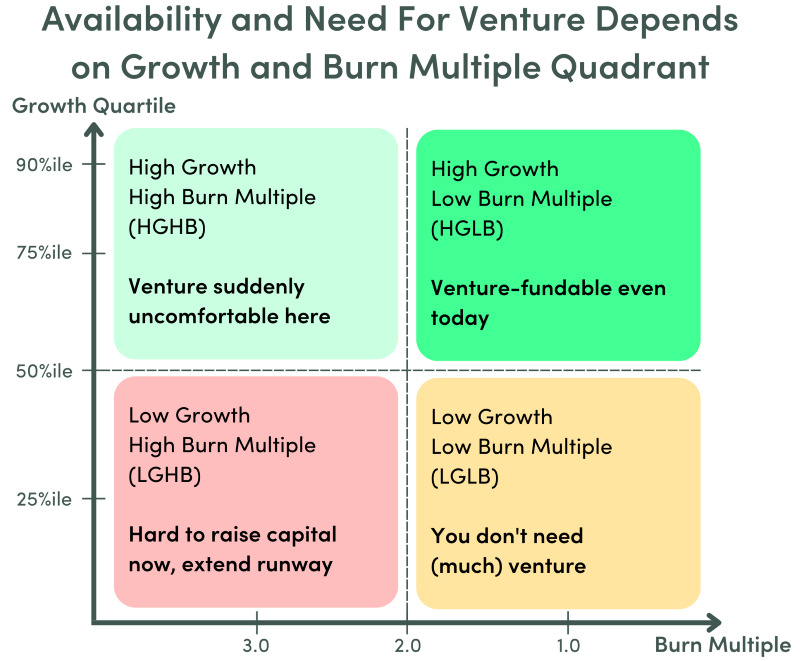

Prioritizing cash runway over growth is the standard venture advice right now. As a practical matter, it is good advice about 50% of the time, half right 25% of the time, and utterly wrong 25% of the time. This is not a bad hit rate, but I think we can do better. The way to do that is not to start on the runway question, “how long do you have” but instead start with the more fundamental question “how strong is your business? “

What is “Good” Growth and an “Acceptable” Burn

The financial profile of any software startup can be characterized at a high level based on revenue growth and either burn rate or burn multiple. This gets complex because what “good” looks like for both metrics, varies enormously by size. A 30% growth rate at $100MM with a burn multiple of .5 would be compelling, but a 30% growth rate at $1M would not be interesting to venture investors almost regardless of the burn multiple. Using data from over 500 companies we have built a set of benchmarks by size from 1MM to 100M+ for both metrics as explained here in detail.

We then make a 2×2 quadrant that shows a specific company’s performance versus the benchmarks. The chart below shows an example, showing two years of numbers (which could be either 2021/22 or 2022/2023).

Different Profiles require different plans

Once you know how your financial profile benchmarks versus other startups, you can make better decisions about managing cash runway. Bluntly this is because you can also figure out how to manage us, the venture industry, the madman in the car. Some companies can ignore venture advice on extending runway but still attract venture capital dollars easily. Some companies have no choice but to optimize for runway because there is no prospect of raising new capital. In the middle, the vast majority of companies have to manage runway as a binding constraint against growth as the long-term objective.

Looking at each quadrant in turn:

Companies with high growth rates and a low burn multiple (HGLB) can continue to grow aggressively and do not need to optimize for runway. These companies will be able to raise capital if required. There is always room in the portfolio for a great deal. Current venture advice is least relevant for companies that are the most interesting for venture investors, which is an odd result.

Companies in the bottom right quadrant, (LGLB) need to aim for cash flow breakeven, ideally without having to raise more capital. If capital is needed the growth profile may not be compelling enough to raise a venture mega venture round, but a smaller round or venture debt should be enough to get the company to break even. It is also possible that post this market craziness, growth ticks up again, so companies at the top end of the quadrant can look to reaccelerate into the top right quadrant.

In the bottom left quadrant (LGHB) the choice is clear. Now is the wrong time to raise money with this profile, so you have to extend your runway regardless of the impact on the business. It may not be possible to build a realistic plan to get all the way to breakeven but what you can do is get time in which to alter the performance of the business and get out of the low low quadrant. We do see companies move quadrants up about 30% of the time on an annual basis.

Burn is not Burn Multiple

The whiplash quadrant is the High Growth High Burn one. Because venture is rightly biased towards growth, companies in this quadrant have been able to easily raise venture money in the last few years often at amazing valuations. Indeed, by pushing capital on companies, the venture industry has effectively forced efficient companies into this quadrant. Now in the space of six months, the rules have completely changed. The advice now is, capital is scarce, cut the burn.

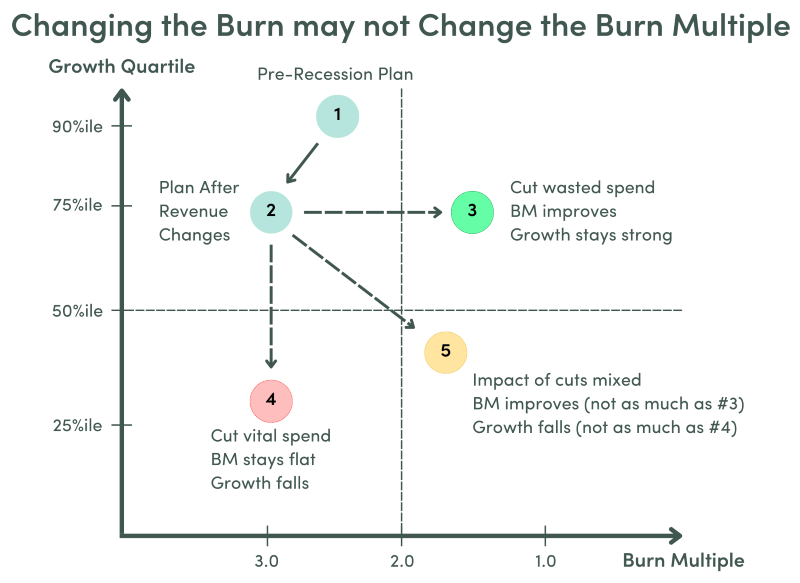

Cutting the burn is simple in a recurring revenue software company. Headcount is by far the largest expense and so the main way to reduce expenses is to fire people. Given the recurring nature of the existing revenue, the burn is automatically reduced. Changing the burn multiple is much harder because it involves reducing expenses without reducing new ARR. The chart below tells the story.

First comes the realization that the FY 22 plan has changed. The growth rate is going down, and unless operating expenses are changed the burn multiple will also go up. The dot has moved from 1 to 2 and the company is going backward on both dimensions. (Ugh downturns are hard).

This drives a replan discussion. The decision is to cut expenses, but the big unknown is what is the impact on new ARR.

- If all the spending being cut was wasted spend, there will be no impact on growth and in terms of the quadrants above the company would just move across to the top right (point 3). This would be a great result but is not likely.

- If all the spending that was cut was vital for growth, then the impact of the cuts is to move the company directly down to point 4. Obviously, this would be a disaster.

- The typical result is a blend where the company improves on burn multiple but also slows down, with the dot gliding slowly down to the right (5). The question is how to evaluate the tradeoffs between runway extension v a reduction in growth to a place that makes the company hard to fund. Cut too little and you run out of cash early, cut too much and you survive but will struggle in the future for relevance and capital.

These discussions get contentious because there are no easy choices. Investors are looking for growth to bail them out on valuation (remember that 123% revenue growth rate to grow into the valuation above) but at the same time, they want to extend the runway to avoid having to raise money. If extending the cash-out date comes at the cost of lower revenue growth, then it gets harder to square that circle.

To avoid confronting this reality investors often resort to the immensely irritating venture advice “sell more and spend less”. Sometimes I think half the money we pay our CEOs is to listen to this s*&t without murdering someone. On the management side, there is always a natural reluctance to admit how much things have changed and how much spending is now wasteful. Wishful thinking meets anchoring.

Tiebreakers: Cash and Valuation

The first tie-breaker is the cash balance. If there is enough cash on the balance sheet to fund a slower march to breakeven, management can get the go-ahead for a less maximalist burn reduction plan in the hope of preserving a higher growth rate. If cash is tight the pushback is often to cut regardless of the impact on growth. This shows that for companies in the HGHB quadrant, the role of luck is real. Two companies with the same business profile can end up with dramatically different realities simply because one was lucky enough to raise last year and one was not. This is not fair, but life is unfair.

The other tie-breaker is valuation. Price clears all markets and the right way to solve a cash runway issue may not be to extend the runway but instead to raise more money, even in a dramatic down round. The job of management is not to preserve the last round price, it is to build a company.

The team at Klarna just did what they had to do to preserve the upside for all investors and even those last-round investors are better off because of the raise. Yes, Softbank looks stupid in the short term but the dilution from the down round is only 10%. If the upside from $50Bn was real before, they still have 90% of that upside. The down round reveals the past valuation error but preserves the chance of future upside. That is the right long-term choice for all shareholders.

Do you like your advice decisive or will useful do?

This is a far less decisive approach than the simplicity of “always cut the burn to be a fully funded plan”. It is a harder approach to implement (different companies get different guidance), and it dials up the risk (follow-on financing, risk of missing revenue). That is the price to pay for preserving the upside.

I think the price is worth paying. Maximizing the runway is not the objective, it is the constraint. If you run out of money you are dead, but if all you do is not run out of runway why bother? The objective is to build a large, sustainable, high-growth business. The challenge right now is not just to survive, it is to survive while preserving enough upside to make the surviving worth the effort.

It is also a humbler approach to giving advice. Investing should teach humility, but venture investors can be slow learners. The lesson of the last two years is how incredibly hard it is to predict valuations, the economy, Covid or pretty much anything. In the face of this, the right advice is situational, conditional and should recognize the risk of bias from the advice giver. Finally, I would say good luck managing right now. You have hit the curse of living and managing in interesting times.

For additional background on the data and methodology behind the numbers in this post, take a look at this post summarizing some of our key decisions and how we arrived at them, as well as more detailed benchmarks.